Remembering Challenger 40 Years Later

The sky over Cape Canaveral was a piercing, deceptive blue forty years ago today. It was the kind of sky that invites you to look up, to dream, and to believe that the limits of our world are just temporary suggestions.

For most of the world, January 28, 1986, is a date frozen in history books. I was already in college but one of my high school teachers was Walt Tremer. He was one of the ten finalists for Teacher in Space. He could have been on that space craft.

Today marks the 40th anniversary of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. While the nation mourns the seven heroes who slipped the surly bonds of Earth to “touch the face of God.”

The Teacher Who Dared to Fly

In 1985, NASA announced the Teacher in Space program. The goal was simple but revolutionary: send an educator into orbit to communicate with students from the ultimate classroom. It wasn’t just about science; it was about democratizing the stars.

Mr. Tremer wasn’t just a name on a list; he was a force of nature in our school in Pennsylvania. When the announcement came that he was a finalist—chosen as one of the elite educators from thousands of applicants—the energy was electric. We weren’t just watching NASA; we were watching him. He went through the screenings, the interviews, and the rigorous selection process that narrowed the field down to the very best.

He often spoke about the “Teacher in Space” program with a mix of awe and determination. He made us feel like our small corner of the world was connected to the launchpad in Florida.

73 Seconds That Changed Everything

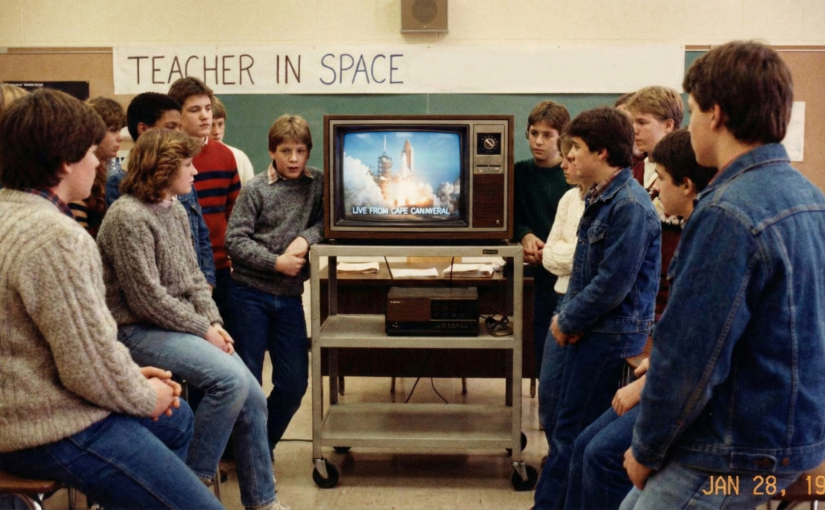

On the morning of the launch, the air was unusually cold in Florida, famously freezing the O-rings that would seal the shuttle’s fate. In classrooms across America, televisions were rolled in on A/V carts. Students watched Christa McAuliffe, the woman who ultimately won the seat, wave to the cameras. She was the “everyteacher.”

And then, 73 seconds into the flight, the cheers turned to confusion, and then to a silence so heavy it felt like it had physical weight.

The announcement came: “Flight controllers here looking very carefully at the situation. Obviously a major malfunction.”

The “What If”

For the families of the Challenger 7—Dick Scobee, Michael Smith, Ronald McNair, Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, Gregory Jarvis, and Christa McAuliffe—the loss was absolute.

For my teacher, Walt Tremer, and for us, his students, the grief was complicated by a chilling realization: It could have been him.

Walt Tremer later described the experience in interviews as being “a phone call away” from that seat. He watched the tragedy unfold with a divided heart—devastated by the loss of his colleagues, yet keenly aware of the twist of fate that kept his feet on the ground.

That kind of “survivor’s proximity” changes a person. It changed how he taught, and it certainly changed how his students learned. We realized that exploration isn’t free. We learned that the people who push boundaries—whether they are astronauts or the math teacher down the hall—are risking everything to expand human knowledge.

40 Years of Legacy

Four decades later, the scar on the American psyche has healed, but the mark remains. The Challenger Centers for Space Science Education were born from that tragedy, continuing the educational mission that Christa McAuliffe started.

As we mark this 40th anniversary, I honor the seven who were lost. But I also honor the teachers like Walt Tremer who raised their hands. They reminded a generation of students that teaching is the most optimistic profession in the world—because it’s always about the future.

We are still looking up, Mr. Tremer. We are still looking up.